EARLY HISTORY

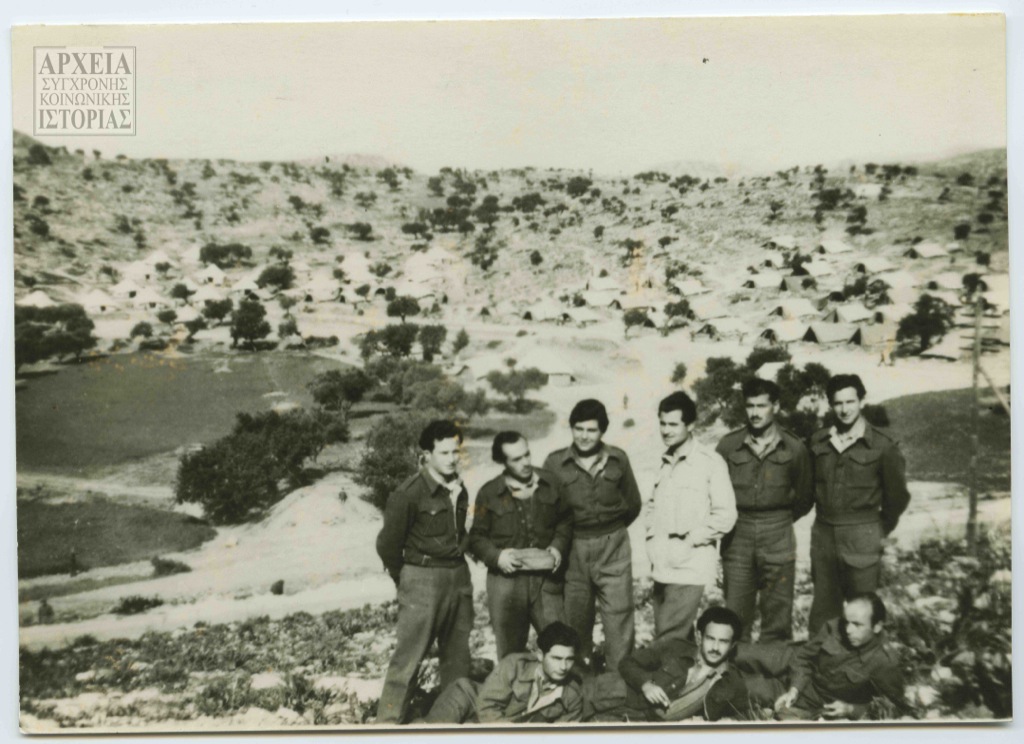

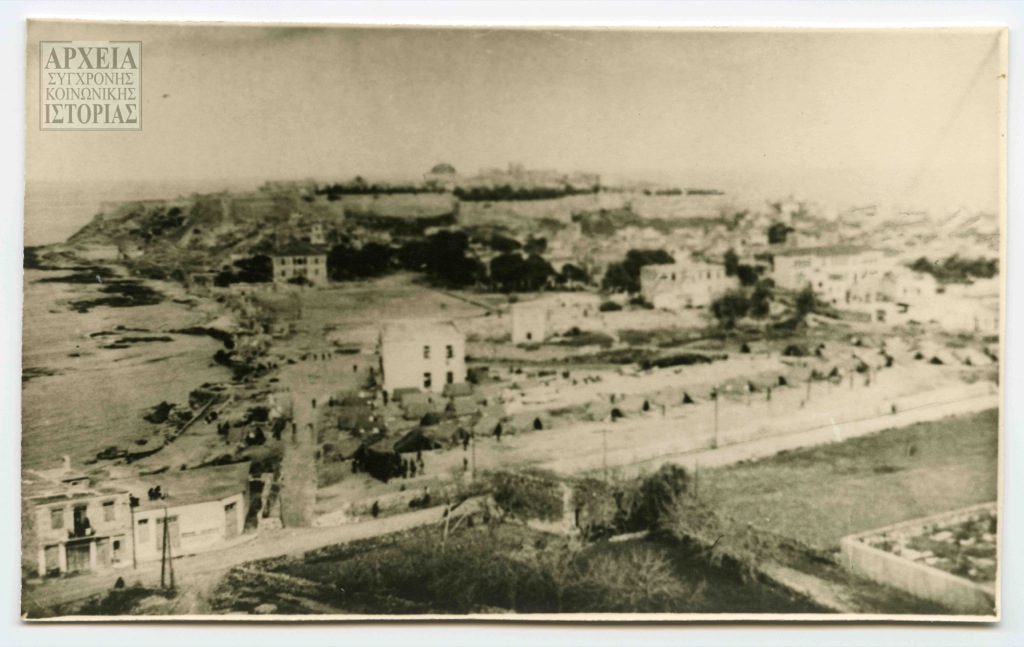

Makronissos is a rugged, deserted island that lays parallel to Attica’s eastern coast. Traces on the island suggest habitation by metalworkers, livestock herders, beekeepers and monks at different, non-consecutive periods. Their presence was linked to the economic and other activity on the nearby island of Kea and in the Lavreotiki area on the Attica coast. Administratively, Makronissos is under Kea, although for at least the last century appears to have been outside any framework – an isolated Aegean “town at large”Scattered cityTerm used to describe the Aegean islands and their nearest mainland coast where there is “perpetual toing and froing of people, goods, and shops from one island to the next in an economic osmosis” (Spyros Asdrachas).. While today it even seems close to Athens, the island has been an outlier, a place of isolation and exile par excellence.

The earliest reference to the island as “Makronissos” is in the 13th century. The island’s elongated shape is reflected in its ancient name, Makris (“Long”), and the later Makri, as it was known from medieval times to the 20th century. The island was also known as Eleni as, according to tradition, the legendary beauty Helen briefly alighted here on the return journey from Troy.

Makronissos sits on a forceful sea currentSea currentThis refers specifically to the cold Pontic current spilling from the Black Sea into the Aegean. Generated by northern and northwestern winds, it flows past Halkidiki and continues south, where it splits into two currents: one flows between Evia and Andros down to the eastern Peloponnesian coast, dividing again into one current that flows into the open Mediterranean Sea and another that flows east to join the Asia Minor current. that flows from the Black Sea into the Aegean. The northern wind, or aparktias (“from the north”) of the ancients, always blew strong in the region; another risk for mariners was the Tripiti shelf extending from the island’s northern point. In antiquity, when sea transport was faster and more practical than overland transport, the area was a popular sea route. Six ancient shipwrecks, dating from the second century BCE to the fourth century, have been identified off Makronissos: two in the Tripiti reef, one at Cape Kentro, one at the Vathi Avlaki cove, and two between Makronissos and Thoriko. The Apollonia VI that ran aground at Tripiti in 1980 is also visible.

In medieval times, Makronissos was a piratePiratesThe pirates active in the Aegean between the 13th and 15th centuries were mainly Genovese or other Italians, Greeks, usually from Monemvasia and Rhodes, and from the 14th century also Turks. Byzantine scholar Michael Choniates refers to the pirates’ rule of the sea as a serious problem in his time and the main impediment to Attica’s food supply. base like the islands of Aegina and Salamina, which also sit off the Attica coast. The Byzantine scholar Michael Choniates, who served as Metropolitan Archbishop of Athens from 1182 to 1204, mentions the impoverished Agios Georgios monastery on Makri, expressing his regret for not evacuating the island to make it less susceptible to pirate attack. There is also a mention of monks in a 1675 account by the French traveller Georges Guillet, while it seems that the Church of Agios Georgios may be the only part of the monastery that survives today.

The French traveller Joseph Pitton de Tournefort, who spent the night of 7 November 1700 on the island, had read in Pliny that rough seas had detached Makronissos from Evia. Nonetheless, the island does not match the geological or mineral characteristics of either Evia or the Cyclades, but does share the same profile as Lavreotiki – albeit with a lower mineral content due to corrosion by rain and wind, with less water and infertile as is usually the case of land with mineral deposits.

Metallurgical activity

Η σελίδα τίτλου της μελέτης του Ανδρέα Κορδέλλα Le Laurium, Marseille, impr. de Cayer, 1869. Bibliothèque nationale de France

In prehistoric times, obsidianObsidianGlass rock from volcanic areas. Obsidian from Milos was used by the Aegean’s inhabitants through the late Mycenaean era (c. 1100 BC) to make tools and weapons. merchants engaging in the trade between the Cyclades islands and mainland Greece would go ashore on the Lavriotiki coast opposite Makronissos, but obsidian blades have also been found on the island. The oldest known lithargeLithargeLead oxide; it was separated into silver and lead through a process known as cupellation, during which the liquid lead was poured into a special cup and oxidised, thus turning into lead oxide (PbO) – called litharge in ancient Greece – while the silver remained unchanged. traces in the Lavreotiki area have been found at the Provatsa site on Makronissos, thus documenting the metallurgical activityMetallurgyThe manufacture and processing of metals and metal mixes from mineral ores. on the island. A small settlement excavated has been dated to 2700–2300 BCE, which is contemporary to the operation of Thorikos Mine No. 3, one of the oldest silver mines in the Mediterranean.

During the systematic miningΜεταλλευτικήΗ εξόρυξη μεταλλευμάτων, ορυκτών και πετρωμάτων. and metallurgical activity in the Lavreotiki area during classical times, which yielded the silver for the Athenian coins or glaukesGlaukesSilver coins minted in ancient Athens with the goddess of Athena on the obverse and an owl, or glaux, on the reverse. The exploitation of the mines from which the silver was extracted spanned the sixth to second centuries BC., there was a parallel activity on Makronissos. SlagsSlagA black, heavy material by-product from smelting for which there was no technological capacity for further use in antiquity but became exploitable in industrial times. Slag, which often contained as much as 12 percent of its weight in silver lead, was utilised in the new metallurgical activity in the Lavreotiki area from 1865 onwards. The area’s mineral wealth by site and type is analysed here: www.mindat.org/loc-14187.html from this period were taken to Lavrio in 1871 for reuse.

In the 19th century, with minerals key to the industrialisation of the West, exploration was intensified around the globe aimed at discovering new mines as well as applying new mining technologies to exploit known mineral deposits. Lavreotiki was thrust into the industrial age thanks to the acumen of the Asia Minor mineralogist Andreas Kordellas, who recognised that the ancient slags could be put to productive use. In 1865, the year modern-day Lavrio was founded, argentiferous lead was once again produced in the area, while in 1885, a rail link was established between the port-town and Athens.

In 1881, Makronissos was ceded as a mine to the Eleni metallurgical company. In 1910, the island was explored for zinc, and just before the outbreak of the Second World War, the Compagnie française des mines du Laurion conducted a geological survey and mapping of the island. In 1948, during the period when the island was used for the “rehabilitation” of political detainees’, the Greek Mining Company Makronissos EMEM SA was founded.

Isolation and exile

In 1912-1913, thousands of Turkish prisoners from the First Balkan War were interned on the island. Following the liberation of Thessaloniki (26 October 1912) and Ioannina (21 February 1913), 26,000 and 30,000, respectively, were taken prisoner and transferred, by sea, to 32 military camps in southern Greece and islands or coastal areas because they were more isolated and thus required less guarding. Records of ship movements from Thessaloniki show there were many prisoner transports for security reasons and problems with food provision even though the agreement on the surrender of the city provided for their stay at Karabournou, a peninsula on the city’s southeast. Prisoner transfers to Makronissos, where the public health service ran an infirmary, began in November 1912. According to French press reports, most of the prisoners from Ioannina were taken to the island, many of whom were already weak and stricken with pneumonia and dysentery.The ill-treatment of Turkish prisoners and locals by Greeks and Serbs was the frequent topic of articles by the French naval officer and novelist Pierre Loti in the French press throughout the winter of 1912–1913. The Staff Service submitted a memo to the International Red Cross assuring compliance with international treaties. Exiles on Makronissos attest to the discovery of hundreds of Turkish graves on Makronissos in 1948 during construction at the military camp. There were also cases of civilians and military officers misappropriating supplies (and, indeed, there were trials in 1915-1916 involving “Makronissos misappropriations”). After the signing of the Greek-Turkish treaty on 1 November 1913, some 10,000 prisoners left for Constantinople.

On 10 June 1922 a decision was taken for the transfer and temporary settlement on Makronissos of refugees from the Black Sea who had begun to arrive in Greece that spring. With the arrival in a single day of more than 8,500 refugees – many sick, with several suspected cholera cases – the Agios Georgios infirmary at Salamina was deemed inadequate and dangerously close to Athens. The issue of the “diseased refugees” was brought up Parliament and raised by the national press.

Οικογένεια προσφύγων, [1922],

On 2 February 1923, in accordance with the Ministry of Military Affairs’ order on the repatriation of Greek prisoners of war after the signing of the Treaty of Lausanne on the exchange of Greek and Turkish populations, provision was made to receive and disinfect them at a military camp set up on Makronissos. However, the “civilian hostages” and the “military prisoners” who arrived were taken to the disinfection station at Piraeus.

In 1931, Makronissos was proposed as a concentration site for communists. In 1935, the press reported that displaced communists would be taken there to minimise the risk of them transmitting their ideas to the Aegean islands.

Related archives

![Νοσοκομείο και λοιμοθαρτήριο για τους πρόσφυγες, [1922]](https://www.makronissos.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Makro1922A-299x206.png)