TESTIMONIES

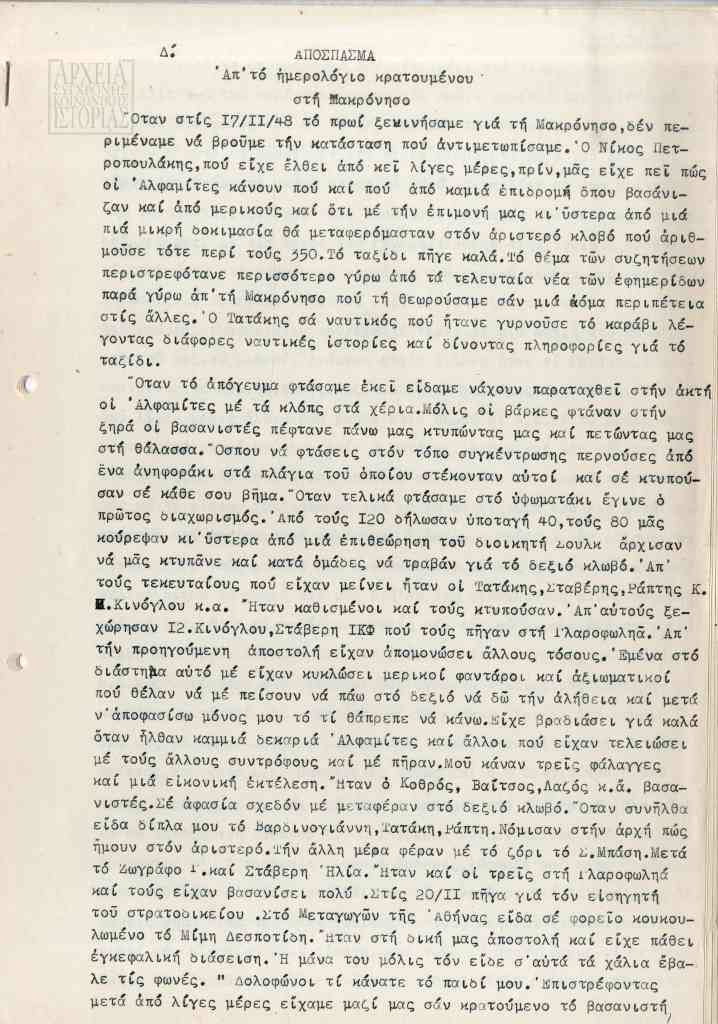

Early on, from June 1947, Rizospastis, the newspaper of the Greek Communist Party, as well as the National Liberation FrontNational Liberation Front (EAM)Broad-based resistance organisation comprising the core of the wartime resistance against the Axis occupiers. From its founding in September 1941, it included organisations, movements and political figures spanning the political centre to the communist left. (EAM) newspaper Eleftheri ElladaEleftheri Ellada (Free Greece)Daily newspaper supportive of EAM; its publication was banned under Emergency Law 509. (Free Greece), published accounts of the dire living conditions and, later, torture at Makronissos military camp. After both newspapers were banned under Law 509Emergency Law 509Emergency Law 509 “on Measures for the security of the state, the regime and the social system, and for the protection of the liberties of the individual”, which came into effect in December 1947, outlawed the Communist Party of Greece (KKE), National Liberation Front (EAM) and National Solidarity, including their publications (Rizospastis, Eleftheri Ellada, etc), these accounts continued to appear in the του Democratic Army of GreeceDemocratic Army of Greece (DSE)The combat arm of the Communist Party of Greece (KKE), it operated from 1946 to 1949. (DSE) Deltiou EidiseonDeltio Eidiseon (News Bulletin)Democratic Army of Greece clandestine party periodical that reported on both military operations and the country’s political conditions, including information on the torture and intimidation at Makronissos. (News Bulletin).

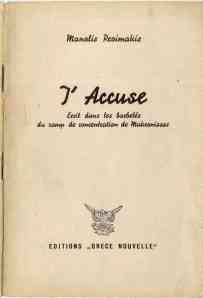

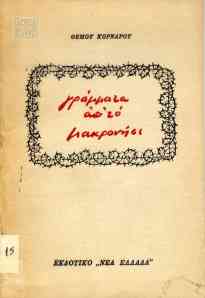

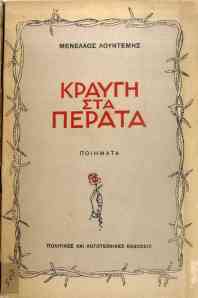

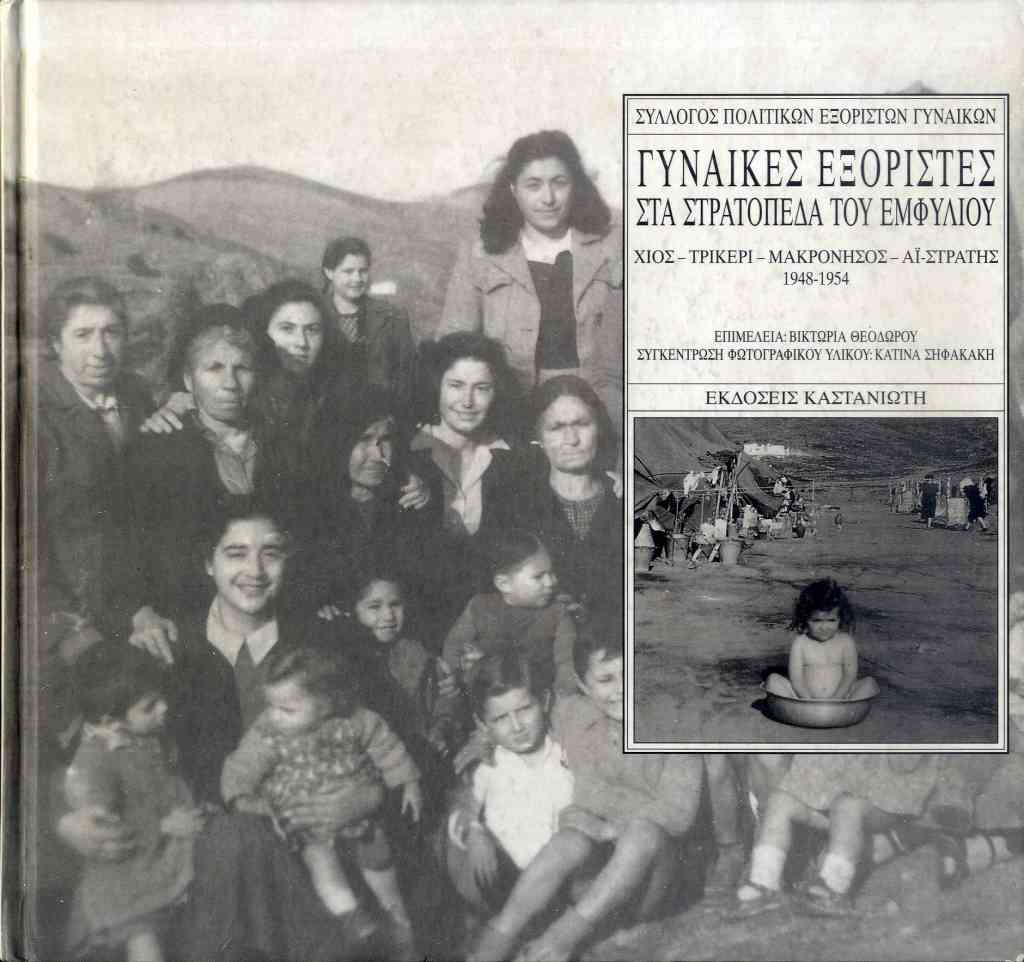

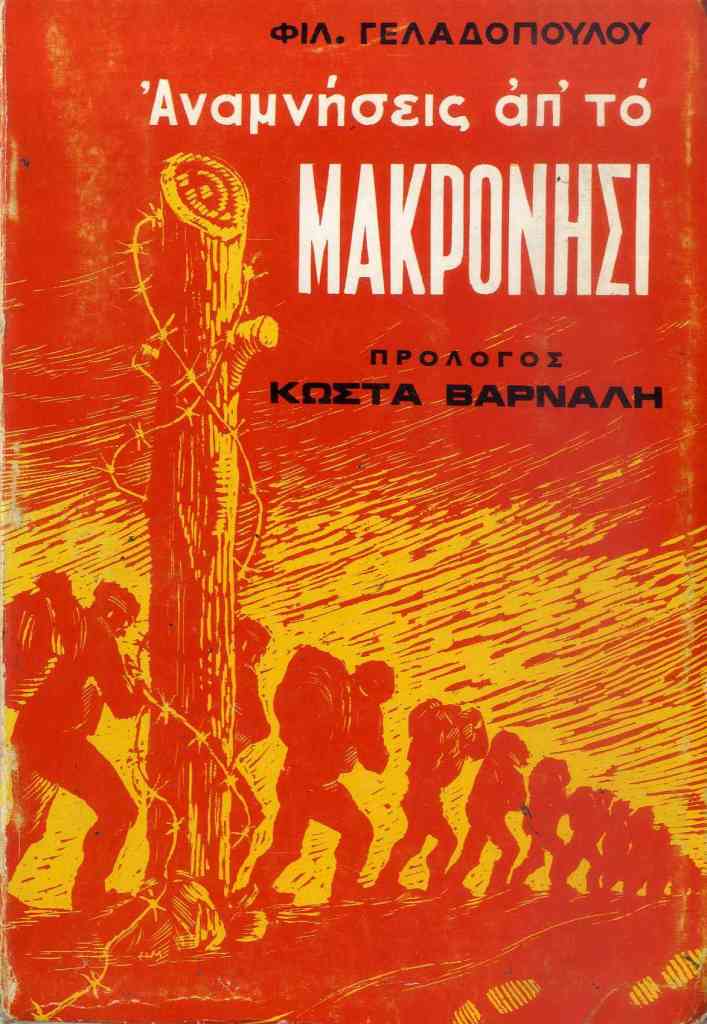

From 1949, an international campaign was mounted aimed at closing down Makronissos. The Communist Party of Greece (KKE) publishing house, Nea Ellada, issued two books that year: Makronisi: H kolasi ton dimokratikon fantaron (Makronissos: the hell of the democratic troops) and Giorgis Lambrinos’ Makronisi: To amerikaniko Dachaou stin Ellada (Makronissos: the American Dachau in Greece). The latter, which was translated into English and French, was widely distributed in the West. The parallels drawn with Nazi concentration camps, particularly Dachau, emerged as the campaign’s rallying cry. Accounts of torture were also aired on Eleftheri Ellada radioRadio station Eleftheri Ellada (Free Greece) /Foni tis Alitheias (Voice of Truth)Communist Party of Greece (KKE) radio station broadcasting from Belgrade and, later, Bucharest during and after the Greek Civil War., the KKE’s radio station that was broadcast from Bucharest.

Meantime, across Western Europe, committees – most notably, in France, the Comité Française d’aide à la Grèce DèmocratiqueComité Française d’aide à la Grèce DèmocratiqueFounded in Paris in 1948 and indirectly supported by the French Communist Party, the Comité promoted the demands of Greek civilian political prisoners and exiles., and in Britain, the League for Democracy in GreeceLeague for Democracy in GreeceIts activities began before the Second World War and continued until the restoration of democracy in Greece following the junta’s collapse in 1974. – mounted active campaigns to abolish Makronissos and draw attention to rights violations and the lack of freedoms in Greece. This activity peaked in the early 1950s, with the publication of several magazine articles by the likes of Jean-Paul Sartre in Les Temps modernesTemps Modernes, LesLeft magazine launched in France in 1945; Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir were among the founding editors. The magazine published exposés on torture at Makronissos. and a piece in New StatesmanNew StatesmanLeft-leaning magazine published in London since 1913 and the first non-Greek publication to report on torture at Makronissos. by Kingsley Martin, who maintained close links with the Labour Party’s left flank.

In Greece, the conditions on Makronissos were shrouded in silence in 1948 and 1949 (as the KKE, EAM, National Solidarity and their publications had been outlawed). With few exceptions, the press was rife with laudatory references to the work being done at Makronissos. In the political climate of the Greek Civil War, marked by suspension of political freedoms and persecution of left-wing ideas, information was shared by word of mouth almost exclusively between relatives of prisoners and leftists, thus establishing – albeit, underground – Makronissos’ reputation as a “hellhole”.

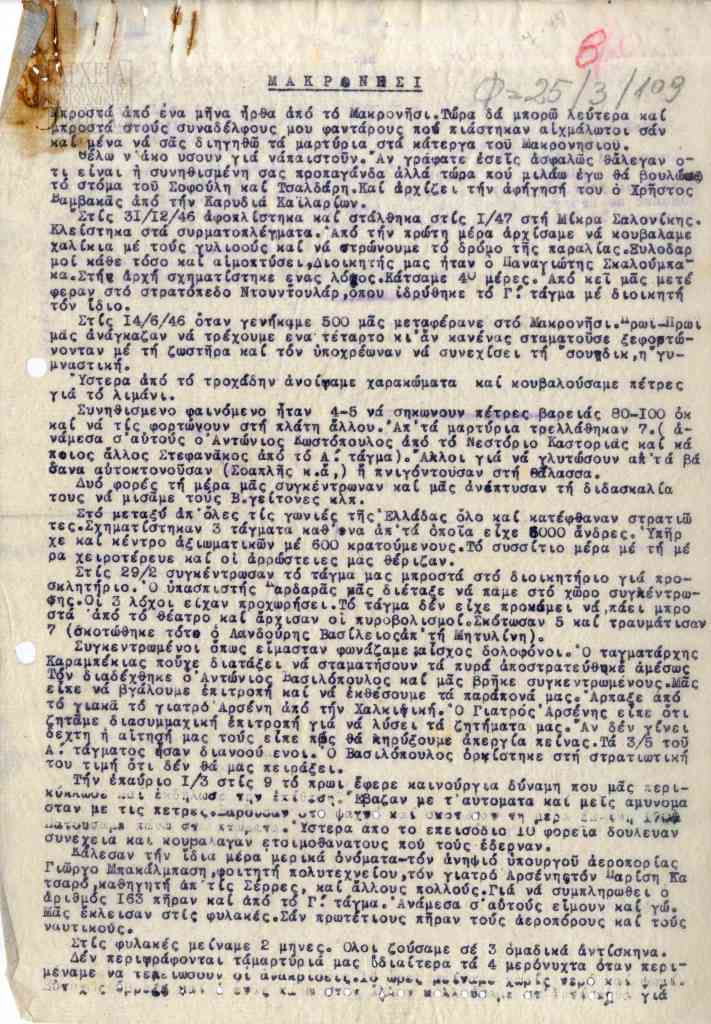

The silence in Greek public discourse was broken in March 1950, just days before the holding of parliamentary elections. The social-democratic newspaper MachiMachi, I (The Battle)Socialist-leaning newspaper published by the Union of Popular Democracy (ELD), which first exposed the torture and terror at Makronissos in 1949. Some of the newspaper’s staff, including Ilias Tsirimokos, were put on trial for these reports in 1950., edited by Ilias Tsirimokos, launched a campaign to close the “hellhole” through a series of articles beginning with the account of Evangelos Macheras, a lawyer and political detainee on Makronissos. The series, published under the header “Behind the blue-and-white curtain”, was largely comprised of letters by current and former prisoners denouncing the inhuman detention conditions and torture to which they had been subjected. The articles caused an uproar – including charges brought against Machi, whose editors were acquitted – as this was the first time that information became available to Greek public opinion about what was taking place on Makronissos. The series ran through the autumn of 1950, but over the summer, the focus was no longer on Makronissos but on Ai StratisAgios Efstratios (Ai Stratis)Island located in the northeastern Aegean; in addition to its use as a place of internal exile, it was where Makronissos detainees who had not signed declarations of repentance were transferred after the Plastiras government introduced clemency measures in 1950. Many of these non-repenters remained there until the early 1960s., another island where some 2,000 political detainees had been transferred, and the prisons.

As a result of these reactions and following the formation of Nikolaos Plastiras’ centrist governmentPlastiras GovernmentIn the March 1950 elections, the Popular Party and the Liberal Party that had led the government during the Greek Civil War failed to win a majority. The newly formed National Progressive Centre Union (EPEK) under General Nikolaos Plastiras, whose central campaign theme had been reconciliation, formed a short-lived government until August 1950. This period was dubbed the “centrist break”, during which clemency measures were introduced for political detainees and exiles. These measures included changes in operations at Makronissos military camp: all troops who had signed repentance declarations and whose class had been discharged were released, as were civilian signatories. Those refusing to sign were transferred to the camp for political exiles at Ai Stratis. on 15 April 1950, Makronissos would become a military camp for left-wing combatants only, not civilians, and conditions in the camp would bear little resemblance to those of the grim 1948–49 period.

Note: All the articles and letters published by Machi have been compiled by Evangelos Machairas in the book Piso apo to galanolefko parapetasma: Makronisos, Yioura, ki alla katerga (Behind the blue-and-white curtain: Makronissos, Yioura and other labour camps), published by Proskinio (Athens, 1999).

Related archives