Why Makronissos

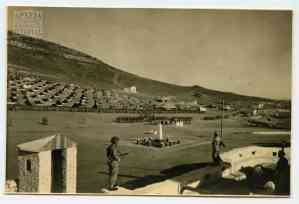

From 1947 until 1961 the island of Makronissos was used as a space of confinement and exile for over 40.000 Greek citizens who were discriminated by the anti-communist State for their political beliefs. The ASKI Digital Museum offers a unique insight in the exile experience illustrating the everyday conditions, the politics of repression, and the traumatic legacies of this important chapter in the lenghty history of state-organized persecution. The establishment and operation of a military compound on Makronissos marked an upturn in conditions of exile existing at the time: an uninhabited area would be “settled” exclusively by exiles, citizens and soldiers, to be “rehabilitated” through an unprecedented programme of propaganda, psychological warfare, and physical and mental torture. The plan had two aims – the professed goal of reinstating the prisoners to the “healthy national body” and a second, undeclared, one of crushing them, thus making it impossible to resume their political action after returning home.

A number of features distinguished Makronissos from other places of exile that came before or after it in Greece: a) The sheer number of political and military exiles. There are no precise figures. Official sources – for example, data provided to the Greek parliament in June and July 1950 by Panagiotis Kanellopoulos and Georgios Papandreou – mention some 40,000 prisoners during the period from mid-1947 to early 1950, and prisoners’ own estimates set the number of exiles for the duration of the compound’s operation (1947–57) at over 100,000. b) The extent and intensity of individual and collective torture. From the hazing and deprivation meted out to detainees when it opened in 1947, the military camp quickly evolved into a centre for systematic, organised torture – physical and psychological. It is especially significant to note that the oppression mechanism was staffed, to a large extent, by “recanters”, that is, former prisoners. c) Makronissos was the Greek national army’s biggest encampment during the Greek Civil War. The detention of thousands of “suspect” youth on the island deprived the Democratic Army of Greece (DSE) of a large pool of recruits. e) As the torture was brought to public attention, culminating in a forceful campaign by the social-democratic newspaper Machi, Makronissos was transformed into an emblematic negative symbol. After April 1950, with the coming to power of the centrist government of Nikolaos Plastiras, Makronissos gradually became a symbol of extreme physical and mental torture, labelled as a “hellhole” and “new American Dachau”, not only within the left but in broader public discourse.

Indicative bibliography:

Polymerēs Boglēs, Stratēs Mpournazos, «Stratopedo Makronēsou 1947-1950. Bia kai propaganda», sto Istoria tēs Elladas tou 20ou aiōna, enotēta D: Anasynkrotēsē, Emphylios, Palinorthōsē, 1945-1952, epim. Chrēstos Chatzēiōsēph, tom. D2, Bibliorama, Athēna 2009, s. 51-81.

Philippos Ēliou, «Ē mnēmē tēs istorias kai ē amnēsia tōn ethnōn», sto Psēphides istorias kai politismou tou eikostou aiōna, Polis, Athēna 2007.

Nikos Margarēs, Istoria tēs Makronēsou, 2 tomoi, Dōrikos, Athēna 1986 [a ekd.: 1966].

Antōnēs Phlountzēs, Sto kolastērio tēs Makronēsou, Philippotēs, Athēna 1984.